On "A Different Man," "The Substance," and the horror of self-loathing

Aaron Schimberg’s tragicomic fable and Coralie Fargeat’s demented fairy tale both explore self-image through satire and body horror, but only the former has the guts to reckon with its subject matter.

“All unhappiness comes from not accepting what is” —A Different Man

“If only her boobs were in the middle of her face instead of that nose!” —The Substance

Our culture is cursed with the need to perfect our imperfections. Ableism, ageism, and capitalism have conditioned us to adopt this kind of thinking, luring us to modify our faces and bodies to make aging and disability seem more like obstacles than inevitabilities. As our identities become more and more centered around how we present ourselves to the world, this impulse to curate a more aesthetically idealized self has metastasized in troubling ways. No more is this evident than in Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man and Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance, both of which were released in theaters a couple of weeks ago.

Though they seem disparate on the surface, both films have surprisingly a lot in common. They explore our cultural anxieties around self-image through darkly comedic satire, body horror, and surrealist allegory. They have their lonely, confidence-lacking main characters make Faustian pacts that will ultimately lead to their undoing. They share a couple of similar visuals and dramatic beats (a shot of a bug inside a glass, a brutal fight between their leads), hip indie arthouse distributors (A24 and Mubi), and most notably, antagonists who represent the protagonists’ “ideal selves” and cause them to double down on their understandable if misguided resentment.

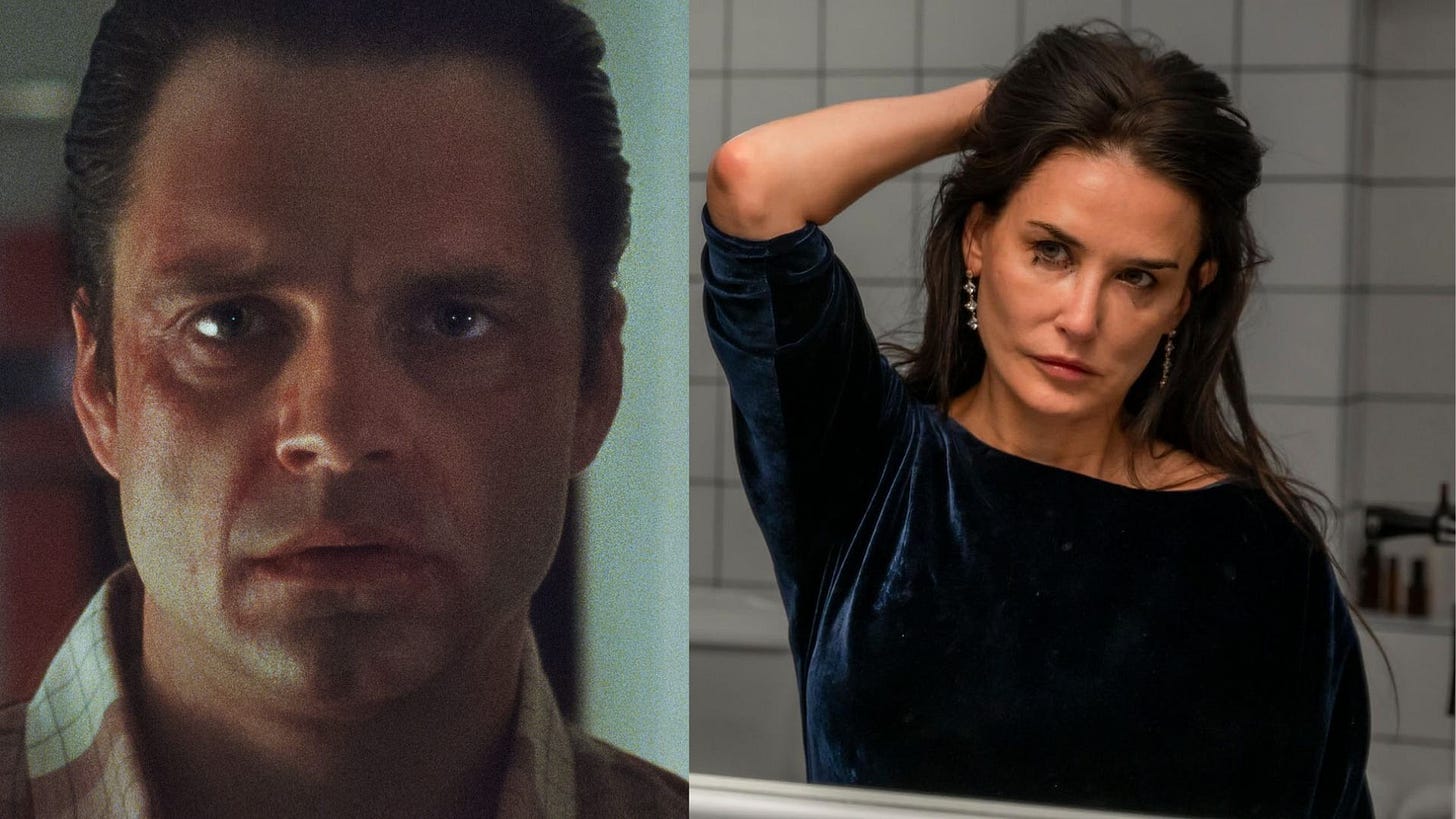

But as the staggering gulf in quality between the lines of dialogue above suggests, these films couldn’t be more different in executing their themes. A Different Man is a subversive, ambitious modern-day allegory about Edward (a career-best Sebastian Stan), a New York-based actor with neurofibromatosis who gets an experimental surgery to correct his facial disfigurement, only to discover that Oswald (Under the Skin’s Adam Pearson), a man with a similar condition, is playing Edward in a stage production about his life, written by Edward’s neighbor/love interest Ingrid (a luminous Renate Reinsve). In extremely stark contrast, The Substance is a cartoonishly over-the-top yet totally empty husk of a movie about Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), a fiftysomething Hollywood actress-turned-fitness instructor who gets her hands on the titular black-market drug that allows her to manifest Sue (Margaret Qualley), a younger, sexier version of herself, but faces physically and psychologically destructive repercussions in doing so.

Though both movies strive to critique Edward and Elisabeth’s environments as the things that trigger them to change the way they look, only A Different Man mines true insight and pathos from our culture’s cruel mistreatment of people’s appearances, which The Substance fails to interrogate coherently and incisively. Part of that is due to the hand with which its filmmakers guide their narratives: A Different Man’s more in-depth, intellectual approach grounds its ideas with a rich, multilayered anchor, whereas The Substance’s blunt-force, smugly abrasive attitude suffocates more than elucidates its thematic aims. But perhaps the biggest demarcator between the two films is the humanity, clarity, and nuance Schimberg brings to Edward’s character, traits that are severely lacking in The Substance’s vicious, sneering treatment of Elisabeth and Sue.

The patient first half of A Different Man shows in direct yet tactful detail how the world around Edward corrupts the way he thinks about himself. He is consistently gawked at and ignored by strangers and frequently mistaken for someone else everywhere he goes. He envies the intimacy between the couples he walks by or sits across from. Despite his passion for acting, the only work Edward can get is performing in amusingly patronizing sensitivity training videos, made for non-disabled people to be more mindful and inclusive to their disabled co-workers. Even the leaking ceiling in his apartment acts as a potentially hostile threat that Edward doesn’t want to deal with fixing, as getting someone to look into it could potentially lead to more unwanted attention. The only person who treats him with any real kindness is the playwright Ingrid, but Edward’s awkwardness around pursuing Ingrid, induced by how degrading his surroundings are, stifles his chances with her.

Building out these elements allows us to immediately understand why Edward ultimately chooses to remove his disability, even though it comes at the cost of renouncing his individuality. A Different Man goes so far as to show how karmically painful and traumatic that renunciation is by portraying Edward’s metamorphosis into a conventionally attractive man as a gradual, unsettling sequence of body horror, with the skin on his face falling off into gloppy lumps until he’s forced to rip the rest off. What’s just as terrifying is the male validation Edward receives once he gets his new look, as he ventures to a neighborhood bar and exercises his machismo with a group of sports bros who burst in to celebrate their favorite team’s win. The beast may become beautiful, but with this new look, Edward becomes a new kind of beast.

Once he completes his transformation, Edward alters his identity altogether rather than simply reintroducing himself, changing his name to Guy Moratz, moving to a more upscale apartment, switching occupations, and developing an active sex life. Despite reaping the cosmetic rewards of a non-disabled person, it becomes clear he made the wrong choice when he auditions for Ingrid’s play and wears a prototype mask of his old face to feel more comfortable in auditioning for the role. Perhaps the irony of his struggling to perform this previous version of himself is a bit on the nose, but the literalization of Edward’s depersonalization nevertheless feels earned because of how much we’ve already emotionally invested in his journey and how strongly it connects to the themes.

In the second half of A Different Man, Schimberg deepens his observations by continuing to make the world around Edward maddening despite his misguided worldview. Case in point: Ingrid’s initial kindness to Edward reveals itself as a kind of benign opportunism, in which she mines Edward’s experience as a disabled person for her own professional and creative self-interest. Additionally, the mischievous yet incredibly self-confident Oswald finagles his way into playing the lead role in Ingrid’s play and sweeping Ingrid off her feet, much to Edward’s chagrin. Even though Edward’s fixation on Oswald’s success seems ill-advised, especially as it inhibits his work ethic and leads him to evolve into the kind of leering stranger he once feared, we still understand Edward’s pain and loneliness. He sees Oswald not only live out the life he wishes he had, but recognizes that Oswald’s able to do so while still having a disability and doesn’t seem to mind being exploited for it to get ahead.

Although some wonky pacing issues and moments of overwritten dialogue mildly threaten to throw A Different Man’s intricate plotting off its axis, what saves the film from flailing is how Schimberg identifies Edward’s fatal flaw — his passivity in cultivating his confidence — and punishes him for failing to be aware of it without making fun of him for it. A Different Man cements this during its brilliant, devastating final note, suggesting that true ugliness is letting the world dictate who we are instead of harnessing what we already have.

The Substance essentially achieves the same message, but through much clumsier, more contradictory means. Fargeat’s demented, maximalist fairy tale paints a paradoxically broad yet unsubtle picture of how the world around Elisabeth informs her insecurities. Unlike the lived-in feel of Schimberg’s casually caustic illustration of New York, the Los Angeles of The Substance is a generic, dated, somewhat confusing caricature of the city. Palm trees, garish surfaces, and sleazy and desperate men are all present, but there’s also… snow on the Hollywood Walk of Fame? Jazzercise is somehow a stepping stone to fame in a seemingly contemporary world? There are billboards that advertise programs called “The Show”? Even if the point is to create a reality removed from our current one, simply depicting shallow people and vacuous places isn’t inherently clever; it’s just lazy and makes it more difficult to buy.

Despite the incoherence of its world, there’s truth to what The Substance is going for — namely, how women internalize the misogyny thrust at them, how older women become more professionally disposable as they get older — and body horror is a perfect vehicle to dig into those ideas. The problem is not only does The Substance display those ideas in the most thuddingly one-note and obvious way possible, but they’re reduced almost to an afterthought in favor of stylistically slick visual tricks. Fargeat’s capital E-Extreme aesthetic choices — intrusive and didactic camerawork, flashy set decor, manic editing, and misophonia-inducing sound design — are relentless to the point of being numbing and diminishing, all shock and no value. The same goes for the gory violence and the icky body horror, which, while entertaining to watch on a surface level and undeniably impressive on a practical one, become fatiguing and unintentionally hilarious at times in their loud, repetitive go-for-brokeness.

At a certain point, the hollowness of Fargeat’s big swings begs the question: What is the point in creating a raw, uncompromising assault on the senses if you’re not going to even be bothered contending with or imagining the larger implications of what’s being dramatized? Why attempt to tackle the subject matter so seriously and earnestly but treat it so facetiously and reductively? Many will argue the lack of subtlety is The Point and is meant to elevate the surrealism of the material. But unlike A Different Man, The Substance’s condescending lack of trust in the audience to Get It makes it harder to emotionally access the story, constantly reiterating the convoluted rules of how The Substance is supposed to work and rehashing exposition and images ad nauseam in case we didn’t understand it the first five times.

The Substance makes it especially difficult for us to care about Elisabeth, who suffers from a similar passivity as Edward but isn’t given enough interiority to make us empathize with her struggle in being seen and desired. She experiences a minor mid-life crisis after her not-so-subtly named TV exec boss Harvey (an unfortunately very fun and campy Dennis Quaid) fires her on her 50th birthday and that’s… pretty much it. In fact, The Substance seems to mock her for being so quick to choose to conform to idealistic beauty standards more than that it seems to deride people who inform that decision, such as the anonymous producers who utter the boobs-nose line or Harvey, who feels less like an antagonistic force and more like a kooky personification of male hubris.

Once Elisabeth takes The Substance, a move that feels rushed more so out of plot convenience than character motivation, Fargeat punishes her for failing to realize her fatal flaw and makes fun of her for it by having her animorph into a decrepit hunchback hag who seethes at Sue for assuming her success. Making a spectacle out of Elisabeth’s misfortune as a way of proving how our culture dehumanizes women creates the same defanging effect as Fargeat’s toothless satire of her world; simply showing something doesn’t equal critiquing it. We understand what Edward gets out of his new look despite the consequences, but what does Elisabeth exactly get out of taking The Substance if she can’t experience any euphoria from it since she and Sue don’t even share a consciousness? Why indulge in the cruelty of her suffering when it’s not all that warranted to begin with?

In the overlong final act, Fargeat forgoes answering those questions to a sadistically self-satisfied degree when Sue experiences the same corporeal deterioration as Elisabeth, takes a shot of The Substance, and manifests a grotesque hybrid of herself and Elisabeth deemed “Monstro Elisasue.” The creature design of the hybrid is impressively ghastly, but it once again demonstrates how muddled Fargeat’s satirical vision is, gesturing at the possibility that the world is to blame for this transformation yet showing that Elisabeth and Sue are the ones who are culpable for it. This could be an attempt at leaving the audience to interpret it for themselves, but without enough compelling emotional context or information, the film collapses under its weight in the same way The Monstro ultimately collapses into viscera, revealing itself to be a revolting spectacle that ultimately has not much going on underneath it.

Perhaps it’s ungenerous to criticize The Substance when it seems tailor-made for a demographic looking for cheap thrills, brightly colored theatrics, and nothing more. And perhaps this speaks to why The Substance’s premise seems more marketable and alluring than A Different Man’s. It promises batshit body horror, hagsploitation, and a sleek arthouse aesthetic (three very trendy things in the contemporary film landscape), as well as a career comeback of a beloved ‘90s actress whose historical backlash for her image brings an intriguing metatextual quality to her performance. The Substance also plays into this growing, depressing trend of Internet brainrot-core, vibes-forward films that seem to be popular nowadays — that is, movies that are deeply out-of-touch yet somehow reflective of the chaos of our current reality, are reverse-engineered to be consumed into memes and merch, and are admired more for their audacity and experiential pleasures than their story, dialogue, and characters.

But the thing is, there’s nothing wrong with imbuing story, dialogue, and characters into genre fare. As evidenced by A Different Man and the many movies The Substance alludes to (e.g. The Fly, Carrie, Seconds, Showgirls, All About Eve, the list goes on), strong writing and a coherent, trenchant point of view can make a film even more haunting and memorable, not less, because we’re able to see our own flaws, cosmetic or otherwise, more clearly. In that sense, this justifies the one point Fargeat manages to get right. Like Elisabeth taking The Substance, our culture prefers something quick and disposable to ease our discomfort with our imperfect bodies and world, even if it’s ultimately not good for us, rather than sit with that discomfort and confront our flaws head-on. Because there’s nothing uglier than the truth.